Immigrant's success was struckwhen pizzelle iron was hot

Posted on 21st Dec 2012 @ 3:34 PM

Thursday, December 04, 2003

By Johnna A. Pro, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Since leaving Lettopalena, Italy, as a teenager, Carmen Palmieri has never wanted to return to the country of his birth. He prefers instead to remember the tiny mountainous village in the Abruzzi region as it is in his mind's eye.

One of the enduring pictures for the 89 year old Palmieri is that of a celebration; a town wedding at which women of the village, including his grandmother, would toss colored almonds, money and pizzelle from their balconies to the revelers on the streets below.

Fiestas in Italy call for luscious sweets, or dolce. In the case of marriages, Christmas, Easter or other religious events, it is pizzelle that marks the day, particularly in the towns dotting Abruzzi, where they have been made for centuries.

The lacy waffle-like cookies that resemble snowflakes or doilies are typically flavored with anise, and their delicate designs are often customized to reflect the particular woman or family who bakes them.

Italian immigrants carried the tradition of making pizzelle to America. Palmieri has played an integral part in keeping the tradition alive for 65 years by manufacturing tens of thousands of handheld and electric pizzelle irons.

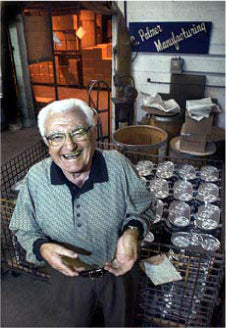

Today, the Palmer Pizzelle Iron is the only American made pizzelle iron on the market. Palmieri, of West Newton, is the godfather of the business. He is a man who is part storyteller, part philosopher and an unabashed, mischievous flirt. At his age, he's allowed to be.

Although Palmieri has turned over day-to-day operations to a younger generation, he still goes to work every day from 7 am to 3 pm. He keeps an eye over the business that started with an experiment in his basement and now includes the manufacturing plant in nearby South Huntingdon and one in Maryland.

"All the things I wanted, my boy let it happen," he said waving his hands expressively and referring to his son John, 65. "You put that in. I started out, but my boy made it happen. The boy and my grandson made it what it is today."

Coming to America

Palmieri was just 15 when he left his mother in Italy and came to the United States with nothing more than a third-grade Italian education.

He joined his father, Giovanni, a naturalized citizen who had come seeking a better life two years earlier.

The elder Palmieri took a job at a coal mine in Westmoreland County. Father and son took on the back-breaking work together after Palmieri lied about his age and got a job there, too.

Just 3 1/2 years later, tragedy struck when Giovanni Palmieri was critically injured at work. He died three days later, leaving his son to make his own way in the world when he was only 18.

Though he lacked a formal education, the young Palmieri had a natural curiosity, innate intelligence and deft hands. He watched other men. He listened. He asked questions. He developed the skills of a master machinist, a talent that would serve him well in the coming decades.

Even with today's 21st-century technology, when equipment at the plant needs to be fixed, adjusted or made to work better, the nine employees can count on Palmieri to study the problem and find a solution.

"He makes everybody's life easier," said his granddaughter, Darcy Palmieri Smouse, who manages the South Huntingdon plant.

Palmieri's abilities were such that the U.S. government granted him four deferments during World War II. They preferred instead that his skills be used toward the massive supply effort under way in the Mon Valley industrial plants, including the radiator factory where he worked after leaving the coal mine.

"I see what other people does, and I learned how to do it," Palmieri said simply and in broken English.

In business for himself

By 1936, Palmieri had married and settled in West Newton with his wife Helen.

Palmieri dug out a basement in their house, and he liked to go there to tinker with tools and equipment. One day he decided to improve a handheld pizzelle iron he had purchased.

He didn't like the design on the metal plates, where the batter was poured, so he decided to make his own.

With nothing more than three sacks of molding sand, 4 1/2 pounds of aluminum, and a coal furnace, Palmieri crafted his own mold with a flower design.

"I changed the design. I didn't like the way it looked. I changed it to suit me; to look better."

He was shaking when it came time to open the mold.

"I hate to open it," he said, laughing. "I didn't want to be disappointed. But I wasn't. It came out good."

The success in the basement gave Palmieri the incentive to produce his own handheld irons. He built his own foundry in the back yard and went to work.

He carried the irons himself by bus or train to the Strip District, where Italian grocers such as Pennsylvania Macaroni and Sunseri Brothers agreed to stock them and advised him about business.

Palmieri streamlined the production process to cut costs, Americanized the name to Palmer and, after some initial mistakes, learned how to price the handheld irons appropriately: $2.50. He was so confident about his work, he offered a 10 year warranty, which the company still honors today.

Before long, Palmieri's backyard foundry was too small for the work. He expanded it twice over the years.

By 1965, Palmieri outgrew the back yard and moved his operations to a modern facility in the rural countryside above West Newton and, with his son's help, transformed the business.

Sand molds have given way to die casts. Computers are an integral part of the operation.

And the tiny coal furnace is now a massive gas fired piece of equipment fed by 1,000 lb ingots of aluminum.

The foundry operations expanded, as did the company's product lines. But while changes have occurred over the decades, the pizzelle iron and variations of it are still part of the company's catalog. This year two new irons were added -- one that makes three smaller round cookies and another that makes three oval cookies.

As he looks back on six decades in the business, Palmieri smiles and refuses to take credit for his success. Above all else, he is a deeply religious man. America, he says, gave him opportunity. But he thanks God for the life he's had.

"You never walk alone, and you never say I," he said glancing upward. "Say we did it. We did it."

Ironing out the technique

Making pizzelle takes some trial and error.

Once you get the hang of it, it's easy and fun. Invite a friend over to help. It's best if you get organized first.

Lay out sheets of wax paper on your countertop or table, so you can let the cookies cool and dry.

Plug your pizzelle iron into an outlet where you will have room to work. Make sure you have a watch or a clock with a second hand. Keep a wet towel handy to wipe your hands.

Plug in the pizzelle iron for 15 minutes, or until hot.

Generously grease the upper and lower grids with vegetable shortening. (Be prepared to grease several times while making the pizzelle.)

Drop a ball of the batter (approximately a tablespoon or just under 2 ounces) onto each grid, slightly to the back of the grid. If you put it in the center or too far forward, it will ooze out. Pull the top of the iron down, lock into place and let each cookie bake for 30 seconds.

Bake the first two cookies and throw them out. (This helps to season the iron.)

Now you're ready to start.

Most pizzelle irons will make two cookies at a time, although some irons will make four and Palmer Manufacturing has two new models on the market that each make three.

After letting the cookies bake, lift the lid. Using a fork or your fingers, gently remove each pizzelle from its grid.

Lay each cookie on wax paper for about an hour to cool and dry. Change the paper and turn each cookie over so the other side dries also. Stack. Freeze or store in an airtight container.

Pizzelle can be served with coffee or dipped in red wine.

— Johnna A. Pro